Decolonising the Mind

by

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o

- The Politics of Language in African Literature

- The essays collected in this volume were previously presented and published elsewhere

- Return to top of the page -

Our Assessment:

B : important arguments, fairly well presented, but too ideologically coloured

Review Summaries

| Source |

Rating |

Date |

Reviewer |

| New Statesman |

. |

8/8/1986 |

Adewale Maja-Pearce |

| TLS |

. |

8/5/1987 |

Chinweizu |

From the Reviews:

- "Ngugi's presentation of the case suffers from a romaticiziation of

the peasantry. It is as if African culture is an exclusively peasant

affair. (...) This misleading bit of Marxist hagiography aside, Ngugi's

book remains invaluable as an African intellectuals account of his

withdrawal from the Eurocentric culture of the neo-colonial state in

which he was nurtured." - Chinweizu, Times Literary Supplement

Please note that these ratings solely represent the complete review's

biased interpretation and subjective opinion of the actual reviews and

do not claim to accurately reflect or represent the views of the

reviewers.

Similarly the illustrative quotes chosen here are merely those the complete review

subjectively believes represent the tenor and judgment of the review as

a whole. We acknowledge (and remind and warn you) that they may, in

fact, be entirely unrepresentative of the actual reviews by any other

measure.

- Return to top of the page -

Ngugi wa Thiong'o famously began his writing career writing in

English (publishing under the name "James Ngugi").

He had considerable success, but eventually turned to writing in his

mother tongue, Gikuyu (though he did translate and publish these later

works in English too).

Ngugi is among a handful of authors who have written successfully in

more than one language -- Samuel Beckett and Vladimir Nabokov are among

the few others -- but his reasons for doing so differ somewhat from

those of other bilingual authors.

Decolonising the Mind is both an explanation of how he came to

write in Gikuyu, as well as an exhortation for African writers to

embrace their native tongues in their art.

The foreign languages most African authors write in are the

languages of the imperialists -- English, French, and Portuguese -- that

were relatively recently imposed on them.

(Ngugi doesn't consider Arabic in the same light, nor Swahili.)

Ngugi makes a good case for the obvious point: that the relation of

Africans to those imposed languages is a very different one from that

which the same Africans have to the native languages they speak at home.

Speaking and writing in the language of the colonisers will naturally be

different than in the language one speaks while at play or with one's

family.

In addition, the language of the coloniser is often a truly foreign one:

segments of society understand it badly, if at all, and so certain

audiences can not be reached by works in these imposed languages.

(The validity of some of these points has, however, diminished over the

past decades, as literacy has spread and French, Portuguese, and

especially English have established themselves as linguae francae across

much of the continent.)

Ngugi rightly complains that an educational focus that embraced

essentially only foreign works (not only foreign in language, but also

in culture) was destructive:

Thus language and literature were taking us further and further from ourselves to other selves, from our world to other worlds.

Clearly there was (and probably still is) a need to create a

literature that conveyed the true African experience -- from the

perspective of the local, not the visitor or outsider.

The local language is an integral part of conveying that experience,

often because much of local tradition has been preserved in that

language -- for example, in the songs and stories that have been passed

down (the oral tradition -- orature -- that Ngugi values so highly).

In the second chapter of this book, "The Language of African

Theatre", Ngugi describes his experiences at the Kamiriithu Community

Education and Culture Centre, and the efforts to stage drama there -- in

Gikuyu.

Ngugi convincingly shows the benefits of working in the local language,

and within local traditions, as the entire community works together to

create and shape a play.

Ngugi's basic arguments are largely convincing, and his personal

experiences, related to explain how he learned and changed his views,

make the entire book an interesting read.

Occasionally he does go overboard: in the end he maintains that it is:

manifestly absurd to talk of African poetry in English, French or

Portuguese.

Afro-European poetry, yes; but not to be confused with African poetry

which is the poetry composed by Africans in African languages.

For new generations the language of the former imperialists has

also become something different.

Admittedly, too often it is the Westernized worldview found in music,

television, and film -- but then the French complain about a similar

cultural imperialism too.

Ngugi is right to say that it is important to reach an audience in the

language of its heritage, but one of the difficulties with that is that

it is financially difficult to publish in local languages in Africa.

The state of publishing is deplorable through much of the continent, and

writers are drawn to English and French also because the audiences (and

publishers) they want to reach are often Western ones.

We at the

complete review are

always terribly disappointed by how difficult it is to find any books

by African authors originally written in an African language.

There are a few, but they are very few.

(Similarly, it is very difficult to find books originally written in

Hindi or other Indian languages, while there are dozens of "Indian"

authors who write in English.)

Ngugi is to be lauded for his efforts in this area, and for his

willingness to stand up for what he believes.

Would that more followed his example.

Among the problems with

Decolonising the Mind is its

political and ideological slant.

He writes of "two mutually opposed forces in Africa today: an

imperialist tradition on one hand, and a resistance tradition on the

other."

Imperialism for him continues after the colonial period: it is "the rule

of consolidated finance capital".

Ngugi's worldview here is still profoundly Marxist, and one has to

question how useful this simple division -- imperialism versus

resistance -- is at the beginning of the 21st century.

(Curiously he chooses to see the class struggle as universal, never

considering that it too might be an imperialist fiction imposed on

Africa despite not fitting African tradition, culture, or history.)

The book also focusses on art-with-a-purpose: be it pedagogic or

political or helping preserve traditions or forge identities, all the

literature he considers serves a purpose.

The simple beauty of art isn't at issue for him -- in part, no doubt,

because he does not want to admit that politically incorrect art (of any

stripe or colour -- even art with say a blatantly imperialist message)

might still have some value.

Decolonising the Mind is an interesting, if occasionally

too heated (and too simplistic) work.

It addresses significant issues, and Ngugi's presentation is

consistently engaging.

Though aspects are already dated, it can still serve as the basis for

fruitful discussion of a subject that continues to be of interest.

1. മോഡറേഷന് പാസും കടന്ന്, തൊഴിലില്ലായ്മാവേതനവും സ്വപ്നം കണ്ട്,

ഭാവിയില് ഒണക്ക പര്പ്പടകപ്പുല്ല് താടിയുംവെച്ച് നടക്കുന്നവനാകുന്നതിനു

പകരം ഹൈസ്കൂള് വിദ്യാര്ഥി എല്ലാ വിഷയങ്ങള്ക്കും നൂറു ശതമാനം മാര്ക്ക്

ലക്ഷ്യമാക്കി അധ്വാനിച്ച് ഉത്സാഹിച്ച് സശ്രദ്ധം പഠിക്കുന്നവനാകണം.

1. മോഡറേഷന് പാസും കടന്ന്, തൊഴിലില്ലായ്മാവേതനവും സ്വപ്നം കണ്ട്,

ഭാവിയില് ഒണക്ക പര്പ്പടകപ്പുല്ല് താടിയുംവെച്ച് നടക്കുന്നവനാകുന്നതിനു

പകരം ഹൈസ്കൂള് വിദ്യാര്ഥി എല്ലാ വിഷയങ്ങള്ക്കും നൂറു ശതമാനം മാര്ക്ക്

ലക്ഷ്യമാക്കി അധ്വാനിച്ച് ഉത്സാഹിച്ച് സശ്രദ്ധം പഠിക്കുന്നവനാകണം.

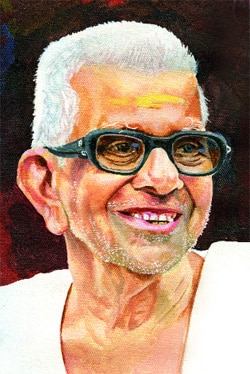

പുരസ്കാരങ്ങള്

നമിച്ചുനില്ക്കുന്ന കാവ്യദര്ശനം... കാലത്തെ കവിഞ്ഞുനില്ക്കുന്ന

കാവ്യസംസ്കാരമാണ് അക്കിത്തം. കണ്ണീരും ചിരിയും ഒരേ സത്യബോധത്തിന്റെ

സ്നേഹാനുഭവമാണെന്നറിഞ്ഞ മനുഷ്യാദൈ്വതം അക്കിത്തം നമ്മുടെ കാലത്തിനു

നല്കി...

പുരസ്കാരങ്ങള്

നമിച്ചുനില്ക്കുന്ന കാവ്യദര്ശനം... കാലത്തെ കവിഞ്ഞുനില്ക്കുന്ന

കാവ്യസംസ്കാരമാണ് അക്കിത്തം. കണ്ണീരും ചിരിയും ഒരേ സത്യബോധത്തിന്റെ

സ്നേഹാനുഭവമാണെന്നറിഞ്ഞ മനുഷ്യാദൈ്വതം അക്കിത്തം നമ്മുടെ കാലത്തിനു

നല്കി... ആത്യന്തികമായി

ഈ സത്യമേ അറിയേണ്ടതുള്ളൂ. അഹന്തയില്ലായ്മയുടെ ഈ അഹംബോധം അറിവായാല് പിന്നെ

തുഞ്ചത്താചാര്യന് പാടിയതുപോലെ, 'തോന്നുന്നതാകിലഖിലം ഞാനിതെന്നവഴി'

തോന്നും. ആ തോന്നലിലേക്കുള്ള വാതിലാണ് ശ്രീമഹാഭാഗവതം. ഭാഗവതത്തിലൊരു

സന്ദര്ഭമുണ്ട്. ഉപനയനം കഴിഞ്ഞിട്ടില്ലാത്തവനും കൃത്യങ്ങള്

നിര്വഹിക്കാനൊക്കാത്തവനുമായ തന്റെ പുത്രന് ശ്രീശുകന്

സന്ന്യസിക്കാനിറങ്ങിയപ്പോള് സര്വസംഗ പരിത്യാഗിയായ വ്യാസമഹര്ഷിപോലും മമത

അടക്കിവെക്കാനാവാതെ, 'ഹേ പുത്ര!' എന്നുറക്കെ വിളിച്ചുപോയി. അപ്പോള്

അതേറ്റു വിളിച്ചത് വൃക്ഷങ്ങളും ചെടികളുമടക്കം സര്വചരാചരങ്ങളുമായിരുന്നു.

സ്നേഹം എന്ന പരമഭാവത്തെ സംബന്ധിച്ചുള്ള ഭാരതീയ ദര്ശനങ്ങളുടെ മുഴുവന്

സാരസത്തയായ ആ വ്യാസശ്ലോകം അക്കിത്തം ഇങ്ങനെ പരിഭാഷപ്പെടുത്തിയിരിക്കുന്നു:

'ആജന്മമുക്തനനുപേതനവന്റെ പോക്കില്

ആത്യന്തികമായി

ഈ സത്യമേ അറിയേണ്ടതുള്ളൂ. അഹന്തയില്ലായ്മയുടെ ഈ അഹംബോധം അറിവായാല് പിന്നെ

തുഞ്ചത്താചാര്യന് പാടിയതുപോലെ, 'തോന്നുന്നതാകിലഖിലം ഞാനിതെന്നവഴി'

തോന്നും. ആ തോന്നലിലേക്കുള്ള വാതിലാണ് ശ്രീമഹാഭാഗവതം. ഭാഗവതത്തിലൊരു

സന്ദര്ഭമുണ്ട്. ഉപനയനം കഴിഞ്ഞിട്ടില്ലാത്തവനും കൃത്യങ്ങള്

നിര്വഹിക്കാനൊക്കാത്തവനുമായ തന്റെ പുത്രന് ശ്രീശുകന്

സന്ന്യസിക്കാനിറങ്ങിയപ്പോള് സര്വസംഗ പരിത്യാഗിയായ വ്യാസമഹര്ഷിപോലും മമത

അടക്കിവെക്കാനാവാതെ, 'ഹേ പുത്ര!' എന്നുറക്കെ വിളിച്ചുപോയി. അപ്പോള്

അതേറ്റു വിളിച്ചത് വൃക്ഷങ്ങളും ചെടികളുമടക്കം സര്വചരാചരങ്ങളുമായിരുന്നു.

സ്നേഹം എന്ന പരമഭാവത്തെ സംബന്ധിച്ചുള്ള ഭാരതീയ ദര്ശനങ്ങളുടെ മുഴുവന്

സാരസത്തയായ ആ വ്യാസശ്ലോകം അക്കിത്തം ഇങ്ങനെ പരിഭാഷപ്പെടുത്തിയിരിക്കുന്നു:

'ആജന്മമുക്തനനുപേതനവന്റെ പോക്കില്

ബോധ്ഗയയില്

നിന്നും ഡല്ഹിയിലെത്തിയ മിംലു ഇന്ദ്രപ്രസ്ഥ കോളേജില് ചേര്ന്നു.

പഠനത്തിനിടെ പരിചയപ്പെട്ട ഒരു ബ്രിട്ടീഷ് പര്യവേഷണ സംഘത്തോടൊപ്പം

ചേര്ന്നപ്പോള് അവള്ക്ക് മുന്നില് ഭൂമിയിലെ അതിരുകള് മാഞ്ഞു.

പാകിസ്താന്, കാബൂള്, ഇറാന്, തുര്ക്കി വഴി കരിങ്കടല് കടന്ന്

ലണ്ടനിലേക്ക് ഒരു ദേശാടനപ്പക്ഷിയെപ്പോലെ അവള് പറന്നു. അല്പകാലം

ലണ്ടനില്ത്തങ്ങി പാരീസിലേക്ക്. കലയും പാട്ടും കാമവും ഫെമിനിസവും നുരയുന്ന

പാരീസ് മിംലുവിനെ അജ്ഞാതമായ അനുഭവതീരങ്ങളിലെത്തിച്ചു.

ബോധ്ഗയയില്

നിന്നും ഡല്ഹിയിലെത്തിയ മിംലു ഇന്ദ്രപ്രസ്ഥ കോളേജില് ചേര്ന്നു.

പഠനത്തിനിടെ പരിചയപ്പെട്ട ഒരു ബ്രിട്ടീഷ് പര്യവേഷണ സംഘത്തോടൊപ്പം

ചേര്ന്നപ്പോള് അവള്ക്ക് മുന്നില് ഭൂമിയിലെ അതിരുകള് മാഞ്ഞു.

പാകിസ്താന്, കാബൂള്, ഇറാന്, തുര്ക്കി വഴി കരിങ്കടല് കടന്ന്

ലണ്ടനിലേക്ക് ഒരു ദേശാടനപ്പക്ഷിയെപ്പോലെ അവള് പറന്നു. അല്പകാലം

ലണ്ടനില്ത്തങ്ങി പാരീസിലേക്ക്. കലയും പാട്ടും കാമവും ഫെമിനിസവും നുരയുന്ന

പാരീസ് മിംലുവിനെ അജ്ഞാതമായ അനുഭവതീരങ്ങളിലെത്തിച്ചു. തന്റെ

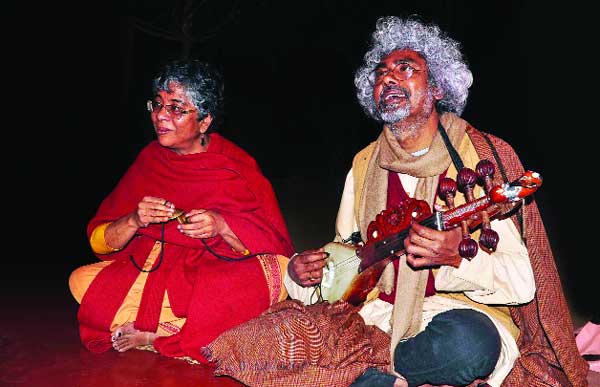

ശബ്ദത്തിന്റെ വില പബന്ദാസിന് അറിയില്ലായിരുന്നു. അന്നന്നത്തെ

ഭക്ഷണത്തിനും അന്തര്യാമിയെ ഭജിക്കാനുംവേണ്ടി മാത്രമുള്ളതാണ് പാട്ട്

എന്നയാള് വിശ്വസിച്ചു. മിംലു പബനെ പാരീസിലേക്കു കൊണ്ടുപോയി. പൊടിപുരണ്ട

ഗ്രാമങ്ങളും ലക്ഷ്യമില്ലാത്ത അലച്ചിലുകളും ഇല്ലാതെ അയാള് ആദ്യമൊക്കെ

അസ്വസ്ഥനായിരുന്നു. അതു മറക്കാനും പബന് പാട്ട് മാത്രമേ

വഴിയുണ്ടായിരുന്നുള്ളൂ. പാരീസിന്റെ രാത്രികളില് അയാളുടെ പാട്ടുകള്

പതിവായി. ആ പാട്ടുകളിലൂടെ ലോകം ബംഗാളിന്റെ ആത്മാവറിഞ്ഞു. പതുക്കെപ്പതുക്കെ

പബന്ദാസ് ബാവുല് പുതിയൊരു മനുഷ്യനായി പുനര്ജനിച്ചു. അപ്പോഴും അയാളുടെ

ഉള്ളില് പാതയോരത്തെ പാട്ട് ശേഷിച്ചു.

തന്റെ

ശബ്ദത്തിന്റെ വില പബന്ദാസിന് അറിയില്ലായിരുന്നു. അന്നന്നത്തെ

ഭക്ഷണത്തിനും അന്തര്യാമിയെ ഭജിക്കാനുംവേണ്ടി മാത്രമുള്ളതാണ് പാട്ട്

എന്നയാള് വിശ്വസിച്ചു. മിംലു പബനെ പാരീസിലേക്കു കൊണ്ടുപോയി. പൊടിപുരണ്ട

ഗ്രാമങ്ങളും ലക്ഷ്യമില്ലാത്ത അലച്ചിലുകളും ഇല്ലാതെ അയാള് ആദ്യമൊക്കെ

അസ്വസ്ഥനായിരുന്നു. അതു മറക്കാനും പബന് പാട്ട് മാത്രമേ

വഴിയുണ്ടായിരുന്നുള്ളൂ. പാരീസിന്റെ രാത്രികളില് അയാളുടെ പാട്ടുകള്

പതിവായി. ആ പാട്ടുകളിലൂടെ ലോകം ബംഗാളിന്റെ ആത്മാവറിഞ്ഞു. പതുക്കെപ്പതുക്കെ

പബന്ദാസ് ബാവുല് പുതിയൊരു മനുഷ്യനായി പുനര്ജനിച്ചു. അപ്പോഴും അയാളുടെ

ഉള്ളില് പാതയോരത്തെ പാട്ട് ശേഷിച്ചു.